This week, we discuss the Simula One's display system, outlining specs in more detail and ending with a video demonstration.

1 Display Specs

| Spec | Value | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 2448(H) x 2448(V) | Number of pixels (measured width by height); often misleading in VR. |

| 1 Pixel = R+G+B dots | 3 dots per pixel | |

| Screen size | 51.78mm x 51.78mm (2.88" diagonal) | Dimensions of each display |

| Pixel configuration | R,G,B Vertical Stripes | Pattern in which pixels are laid out on screen (see below) |

| Pixel pitch | 21.15um | Distance between pixels (see below) |

| Number of colors | 16,777,216 Colors | 1 byte per color dot => 28 = 256 colors per dot => 2563 = 16,777,216 colors per pixel |

| Weight | 10.7 g | 2 displays => 21.4 g of weight. |

| Contrast ratio | 650:1 | Ratio of the luminance (or brightness) of all white pixels to the luminance (or brightness) of all black pixels |

| Refresh rate | 90Hz - 120Hz | How many times per second a display is able to draw a new image. |

| Response time (BtW) | 5ms | How long it takes for a pixel to go from black to white. |

| Typical brightness | 150 nits | Brightness of the display under normal settings |

| NTSC Color Gamut | 83% | Percentage of NTSC color gamut capable of being displayed |

If you're new to displays, some of the terms mentioned above (e.g. "dots", "pixel configuration", "pixel pitch") might need clarification:

- Pixels vs. dots. Dots (also known as "subpixels") are single-color subregions of a pixel. Depending upon the pixel configuration of the display, dots can show up as small lines or small circles assembled into various patterns (e.g. vertically aligned lines, staggered circles, etc).

![]()

- Pixel configuration. Pixel configuration (or "pixel geometry") refers to how the dots in a display are patterned.

![]()

- Pixel pitch. Pixel pitch measures the distance between pixels (or between dots of the same color) on a display.

![]()

-

Computing the number of colors. The number of colors displayable is determined by the bytes allocated per pixel. In our case each pixel has

3dots (R+G+B), and each dot has8bits (or1byte). Hence each dot can encode2^8 = 256distinct color values. Since there are3dots per pixel, each pixel is then capable of displaying up to256^3 = 16,777,216distinct colors. -

Response time (BtW). Response time measures how long it takes for a pixel to change colors (in this case: from black to white). This serves as a proxy for how long it will take for a display to draw a new image after it receives a new draw. Low response times are crucial for responsive VR, while high response times can cause disorientation or motion sickness.

-

NTSC Color Gamut. The NTSC color gamut denotes a subset of the visible color spectrum which displays can benchmark against. In our case: our displays are capable of showing colors from 83% of the NTSC gamut.

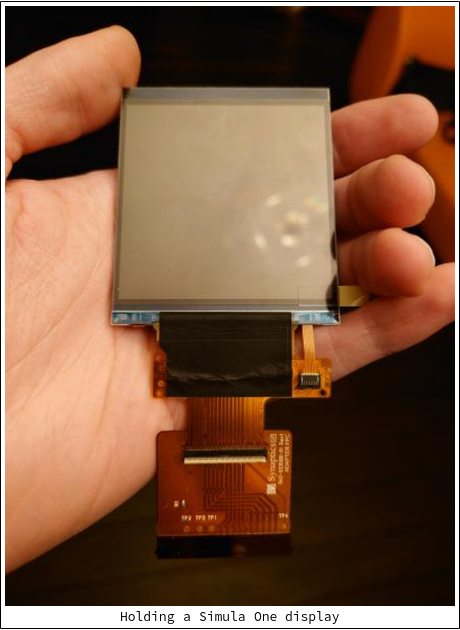

2 Integrating the displays into our headset

The process of connecting a Desktop PC to a display is pretty straightforward: simply connect them together with an HDMI or DisplayPort cable. However, panels are rarely driven directly by DisplayPort.

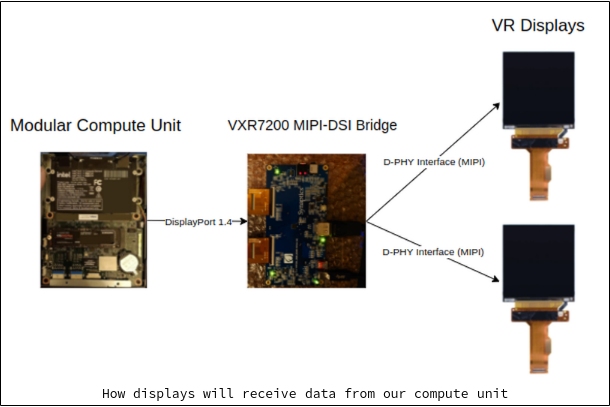

- Each of our two VR Displays expects to be connected via the MIPI-DSI Serial Interface (a pretty common standard for mobile & VR displays).

- The CPU in our compute pack only provides a single MIPI-DSI port, but we need two!

- Desktop PCs do not support MIPI outputs, so you wouldn't be able to use the displays in tethered mode

Our solution to (1)-(3) is to split up a single outgoing stream of DisplayPort data into two MIPI-DSI lanes, via a VXR7200 Dual MIPI VR Bridge. With two MIPI-DSI streams, we are then able to connect them to each of our VR displays.

Here's what the VXR7200 looks like (using an evaluation board):

The overall connection setup can be visualized roughly as follows:

Note that the D-PHY interface connecting the bridge to each of the displays is a type of a MIPI interface.

3 Testing the displays

Putting this all together: below is a video of our compute unit routing video data through the VXR7200 bridge to our displays:

Note that the images in our VR displays still need to be distorted for them to look correct when viewed through our lenses (details discussed here). This distortion will be handled through a library called monado, which is an open-source implementation of an OpenXR runtime. We will explain these issues in more detail in a future post.